The Royal Zenana Mirror: A Miniature Painting’s Secret

Share

We’re thrilled to share a beautiful piece from our growing collection at Purathanam—a captivating Rajasthani miniature painting, created in the 1970s–80s in Jaipur, Rajasthan. This artwork captures a quiet, graceful moment inside the royal Zenana.

Now, you might wonder, what exactly is a Zenana? When I first came across the term, I thought it was the same as a Harem. And honestly, I wasn’t entirely wrong but there’s a subtle difference. Let me explain that before we dive into the painting.

In the Middle East, Harem is more commonly used during the Ottoman Empire. The word comes from the Arabic ḥarīm, meaning “forbidden” or “sacred/ private.” This term Harem rooted in Arabic and Turkish culture, often gets sensationalized in Western narratives. For instance, colonial-era writers, travelers, and artists from Europe, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, painted the harem as an exotic and mysterious world filled with beautiful women kept for a king or sultan’s pleasure. At its core, it simply referred to the secluded quarters of a household reserved for women.

In South Asia, especially during the Mughal period, the word Zenana served a similar purpose. It referred to the private quarters of women in a household, usually royal or noble ones. Like harems, zenanas were protected, secluded spaces where only selected individuals were allowed in, usually female attendants, eunuchs, or close male relatives. The word Zenana is of Persian origin and is deeply rooted in the Indian subcontinent, particularly in Mughal, Rajput, and Deccan courts.

The Zenana was originally part of Indo-Islamic culture and was mostly seen in aristocratic Muslim homes. But over time, with Hindu-Muslim exchanges, even upper-class Hindu families started adopting it, influenced by elite cultural trends. And it wasn’t just a space for seclusion, it was also a place where women were educated, where art and culture thrived, and where quiet influence took shape. History tells us about many strong women from these inner worlds like Nur Jahan, Jahanara Begum, and the queens of Rajput courts who played important roles behind the scenes

So yes, the Zenana and the Harem are conceptually similar like cousins, perhaps. They served similar functions but came from different cultures and carried their own unique personalities and rich historical contexts.

Now, let’s return to the painting…

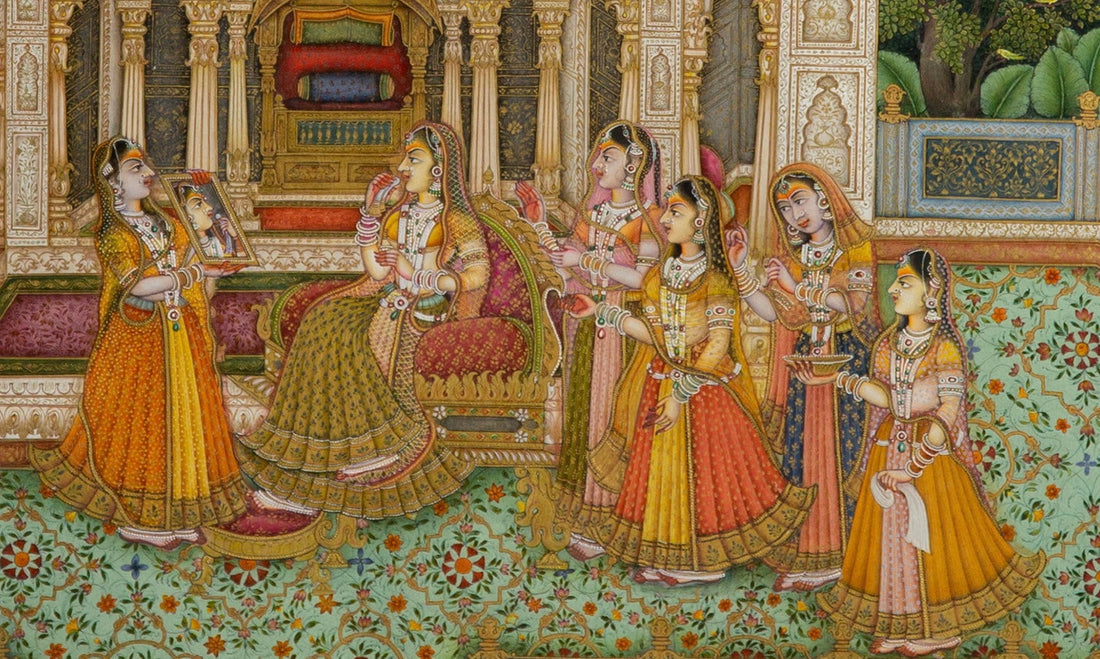

This beautiful miniature captures a serene moment from a royal zenana—the women’s quarters of a palace. A queen or princess sits in her garden courtyard, surrounded by her companions and attendants. One holds up a mirror, another brings a bowl of water, and perhaps a piece of muslin cloth, while others look on curiously, eager to know what happened to their Queen/ Princess. The atmosphere is gentle and intimate, full of elegance, warmth and quite the beauty of life behind palace walls.

Curious about what this royal zenana scene might be about?

Thankfully, the artist has described the moment in Devanagari script at the bottom of the painting. It’s poetic couplet, playful and delicate, bringing the scene to life with humour and charm. Suddenly, the scene isn’t just something to look at, it becomes a living, breathing moment, full of intimacy and personality.

Here’s how the poem goes in Devanagari;

Transliteration:

“Yah jo īkā dārpaṇ dekh vahī so beṭī rikaṭī kā praṭibimba dṛṣṭi paṛat so lī kā koṁ chaṁkaṭ moṭī mānas hīṭ sāla khōṁṭak kapāṭ bhī haiṁ

Sau sau bhīnāp kā śuka kahat hai, yeh hī so patī paṭsāhīn jānī patīhīn pratibimb haiṁ.”

It describes a playful and gentle moment. This scene isn’t just about royal life, it feels like poetry in motion. The verse on the painting draws our attention to a small beautiful detail: the white reflection of the queen’s Pearl nose ring has fallen in her lips. She sees it in the mirror and, thinking it’s a limestone stain which women used traditionally while chewing betel leaves, she tries wipe it off.

Her friend, amused and observant, gently says:

“O clever one, this is not lime. It’s the reflection of the pearl. A cloth won’t erase it.”

In that moment, the queen doesn’t feel distant or royal, she feels real. A graceful woman, slightly self-conscious, sharing a light moment with her friend. The painting shows their bond, filled with beauty, warmth, and affection. It brings us closer to a world we usually see as formal and far away.

That’s the magic of miniature paintings. In such a small space, they hold not just colors and details, but emotions and life. Without that little note, this would’ve been just another lovely painting. But now, the painting speaks for itself!

A big thank you to Dr. Riddhi Patel and her kind father for helping me with the transcription. I’m dedicating this blog to the artist who added that small poetic touch someone who didn’t just paint a scene, but captured a feeling.

The History and Technique of Miniature Paintings;

Miniature paintings flourished under the Mughal, Rajput, Pahari, and Deccan courts between the 16th and 19th centuries. Artists used natural pigments and fine brushes often made from squirrel hair to paint on surfaces like paper, palm leaves, or even ivory.

This particular painting was made using watercolors and real gold leaf on paper. It follows the classic miniature tradition, known for its intricate details, fine lines, and graceful elegance. Every fold of fabric, every carved pillar, is painted with care. The floral carpet, the garden courtyard, the soft gestures all of it reflects the heart of India’s miniature art: small frames, big stories.

Want to take a closer look? Click the links below to explore the Royal Zenana and other miniature paintings from the Purathanam collection.

- The Royal zenana - Miniature Painting

- The Cosmic Darbar - Miniature Painting

- Krishna Leela - Miniature Painting